A new training request has arrived in my inbox: Employees aren’t selling enough of Product X, so they need more training on the product.

Do they?

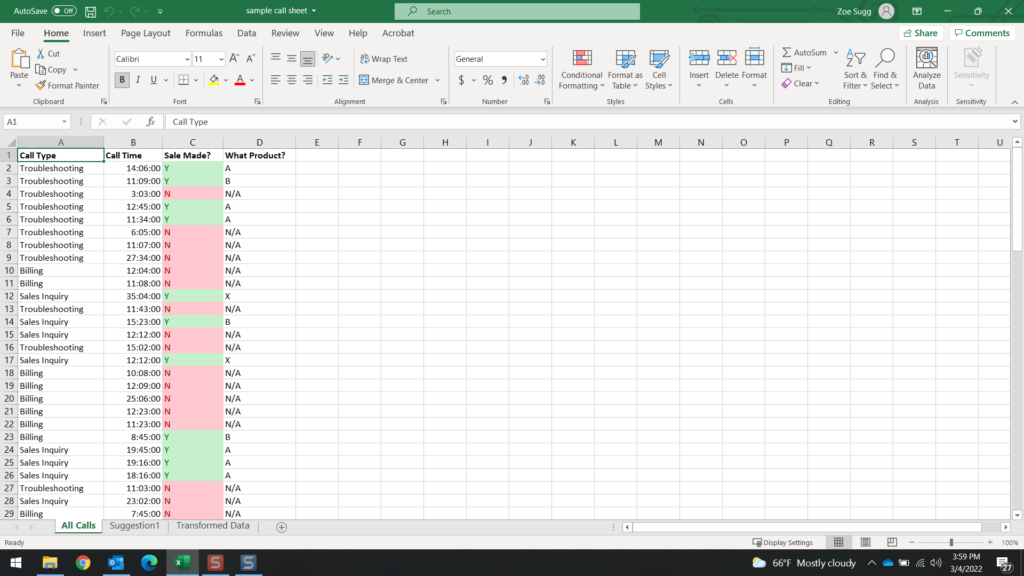

This is a common example of the kind of request that often lands on my desk, and it’s a perfect example of how I use the “analysis” step in the ADDIE model. I created this sample problem to show how I might “Analyze” an ask for training. We’re going to work through a hypothetical model using fabricated data from 100 contacts coming into a call center. In the real world, I’ll likely have a lot more data that’s a lot less tidy, but this is an exercise, so I kept it nice and clean. I decided to use mock examples, since it’s a little difficult to scrub an entire analysis process for sensitive information.

So, let’s say I’m at a call center that focuses on some type of sales in addition to it’s usual tech-troubleshooting work. As per usual with training requests, the inquiry is vague: Employees need training on Product X. We’re going to go ahead and say the kickoff meeting doesn’t return much more information than that (partially to save time and partially because “Discovery Meetings” could occupy several entire articles by themselves). All my stakeholders know is that employees need to sell more of Product X, so they suggest I build a training to catch them up on the subject. It is up to me to figure out if the employees actually need training.

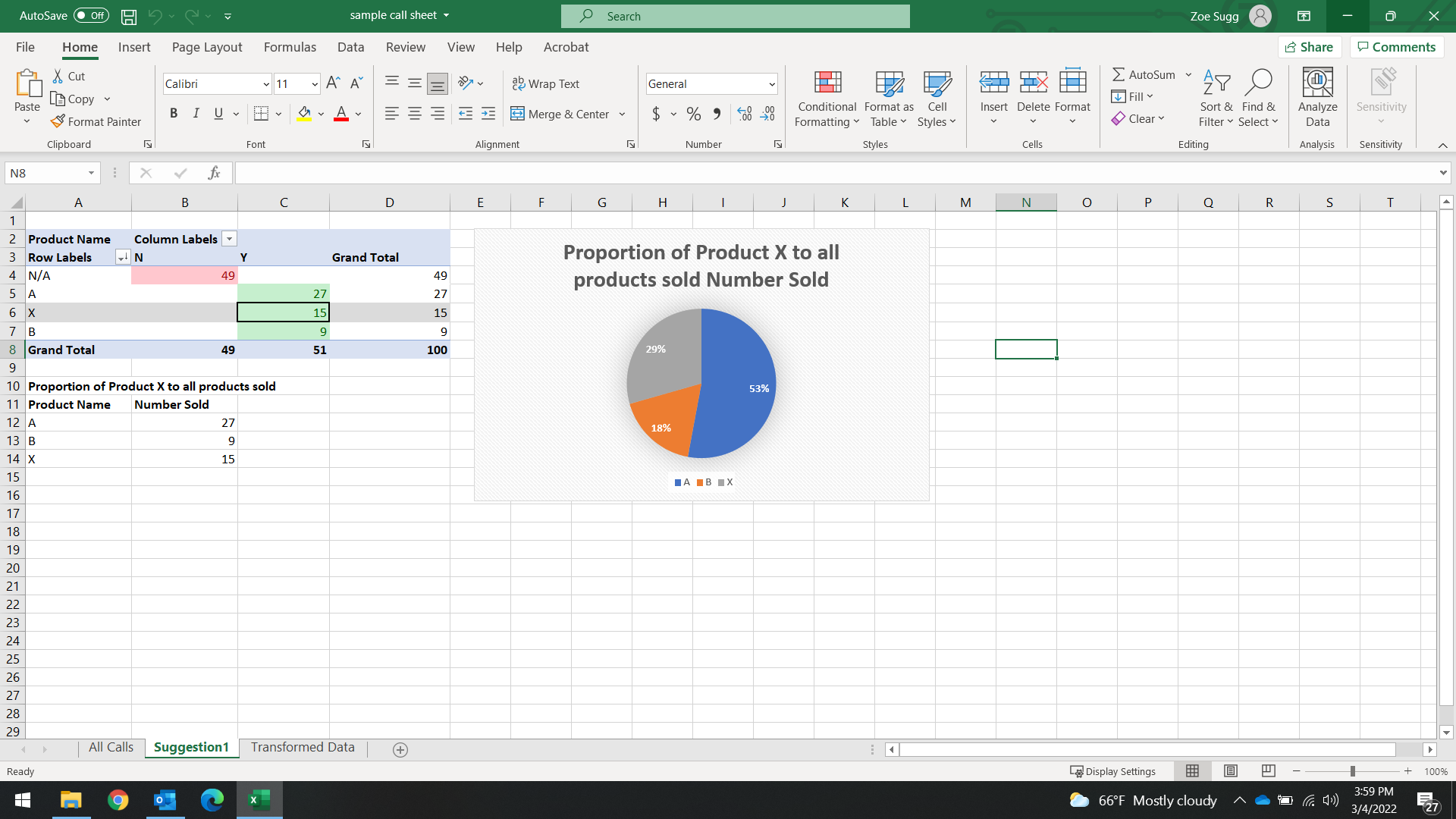

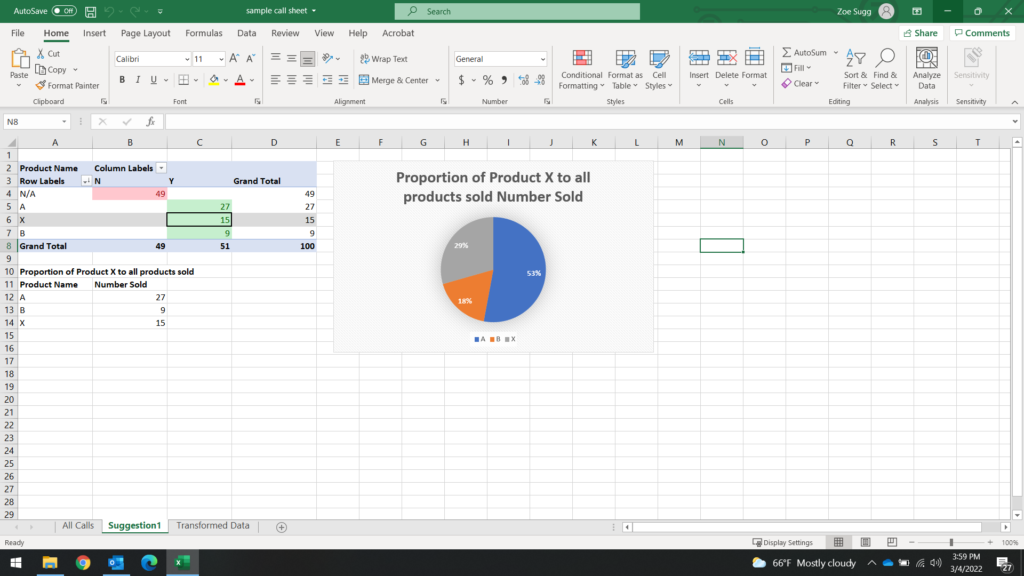

First step is to see how much Product X we’re actually selling – according to a sample of data I pull, 29% of all products we sell are Product X. It’s nothing to sneeze at, but when we launched Product X, we expected it to skyrocket to the top of our sales. I see that Product A, though older, is still defending its spot on the leaderboard at 53% of our sales. Product B is a niche product. We’re not expecting it to ever surpass the others in sales, but it’s good we’re offering it, so it’s fine where it’s at.

Next step is to pull all the calls that sold Product X. It’s only 15 calls so if I have time, I’ll listen to all of them. Depending on the deadline though, at least 5 calls is my target.

I do manage to listen to all 15 calls, and what I find is that they go rather according to plan! The salesperson pitches the features of Product X, finds ways they will benefit their customer, and gets them to agree to the purchase. They follow the company-approved sales model, which I already have training material for, so I don’t really need to expand or improve on anything here.

But wait- what about the calls that are marked no sale? I realize that not only do I need to track what works for selling Product X, but I need to find out what calls had Product X pitched to the customer, but didn’t move forward into an actual sale.

Getting data for this might be a bit trickier: If my company’s using an advanced tracking system, I could pull any calls that mention Product X in the notes, or look for a feature that actually tracks unsuccessful pitches. Most of the time I’m not fortunate enough to be able to pull this data, so it’s back to the anecdotal side of things: pulling coaches and asking what their coaching conversations look like when Product X doesn’t sell, or pulling a focus group of sales agents to tell me how their conversations with customers go when they attempt to pitch Product X. Of course, the more combined methods I can get my hands on, the better. It all depends on time and resources.

One way or another, let’s say I find out that most of the time when Product X doesn’t sell, it’s because it doesn’t have a specific feature- Let’s call it Feature 1.

I ask my agents what happens when a customer needs Feature 1- do they simply drop the sales conversation, or do they find another solution for their customer?

As it turns out- they do have another solution ready! Product A is the only product our company offers which has Feature 1. The developers for Product X are in the process of trying to include Feature 1 in the next update, but as of right now it doesn’t exist anywhere else at our company.

Time to confirm that anecdotal data. I don’t have time to listen to listen to nearly 30 calls, but I do have an idea of what I’m listening for, so this could go a few ways:

- Listen to a good sample size of the calls- something like 7 of them so I have at least 25% of the calls. See how the conversation covers Features, and look for a part where Feature 1 shows up, or listen to a transition point from Product X to Product A

- Listen to a portion of all the calls. Because I know the sales process and have an idea of where the “features and benefits” part of the conversation is, fast-forward to about halfway through the call and listen for a part where Feature 1 shows up, or listen to a transition point from Product X to Product A

Sure enough, I find several examples where the employee had to pivot away from Product X due to its Features, or the customer brings up Feature 1 organically and the employee’s only choice is to showcase Product A.

It’s important that I document as much of this as possible, because in this situation I really don’t need a training on Product X. Any of the sales calls that successfully moved it are using our recommended process; I can’t really add anything to their experience by creating more training. The reason Product X isn’t moving as expected is because of Feature 1’s absence. It’s possible I could be directed to create “something” to help move Product X along, as a show of good will to the Sales and Development departments. Office politics are a thing of course, and the Learning and Development leadership probably wants to demonstrate that we’re willing to help, even though we can’t really make much of an impact. In this case, there’s probably an announcement board or newsletter that goes out to employees, and I can create some sort of refresher sheet or spotlight on Product X to sort of “cheerlead” for it and remind our employees about its great features and benefits.

You may be asking, if you’re newer to the industry and you’ve gotten this far through the article, “Why is any of this the ID’s problem?”

It’s a fair question. We’re paid to be knowledgeable about learner psychology, not sales data. Is it our responsibility to question leadership over a training they’ve requested, when we know training isn’t the problem? If that sounds unpleasant to you, you’re not alone. Because let’s face it, I’m about to take what I’ve found back to a team of developers who no doubt already understand that Feature 1 is an issue that needs to be solved ASAP, and they’ll probably be a little grumpy when I present the data to leadership. That’s where the “cheerleading” spotlight material comes in handy- I’m able to show some good will on my part by creating something that praises Product X’s features and promotes its sale, showing the product owners and developers behind Product X that I believe in them and their work- essentially, this is a safeguard against anyone thinking I’m trying to avoid work by throwing these teams under the bus.

Still there are others in our field who will opt to keep their heads down and build a new training module all about Product X. After all, even if the data is on our side, is it worth sticking our collective necks out for this?

I say yes, and the reason I do so can actually be quite self-serving! It’s not because I think I’m some great crusader for Learning & Development, or that I’m so invested in our learners’ time and cognitive load (although those are both important!). It’s because I’m passionate in showing L&D’s return on investment. Learning and Development isn’t an industry that always directly correlates to sales, and let’s face it, it’s an often understaffed department and one of the first to come under fire when the company’s not performing well. So how do we, as Instructional Designers, protect ourselves from that? We constantly need to demonstrate our ROI. And the only way we can show a positive impact on the company is if we accept appropriate projects, with problems we can actually hope to solve through training and reinforcement of good habits. I wanted to set aside some time to show what a realistic level of analysis is in my experience. Like I said, this is extremely tidy data, and very simplistic. We don’t have dropped calls to sort through, or a ton of outliers. We also have this data readily available, and in a perfect world we could drill down and pull out a lot more information than just what I’ve shown here. However, this is a decent example of the kind of intuition I have to demonstrate, and compromises I have to make, when discovering that a request for a training initiative may not pan out the way my stakeholder(s) expect.